The video opens with a shot of a cheerfully earnest young woman in a pizza store. “My name is Crystal,” she says directly into the camera. “I’ve been working for Domino’s for 8 years. A lot of people think I’m just a punk teenager making pizzas, but that’s just not true. I also have a degree in watercolor.”

She’s no actor, but a real employee. We see her painting in her bedroom, meticulously producing whimsical still lifes and colorful self-portraits. “I want people to see that I care about my art and the craft that goes into pizza making,” she says. At the end of this simple story, we learn that she’s now a General Manager and hopes to open her own franchise one day. It’s all part of a video series called “Handmade by Domino’s” that launched earlier this year, and which also introduces us to Chris, whose hobby is glassblowing, and to Diego, a muralist, both of whom are Domino’s pizza makers.

They’re simply an extension of one of the most successful marketing campaigns in recent memory. It began, famously, in 2009 when Domino’s introduced a new pizza recipe and CEO Patrick Doyle took the unusual step of appearing in TV commercials to offer customers his humble apologies that the old recipe hadn’t been very good. In the first quarter of 2010, Doyle’s heartfelt requests for a second chance earned Domino’s the largest single-quarter revenue boost in the history of the fast-food industry.

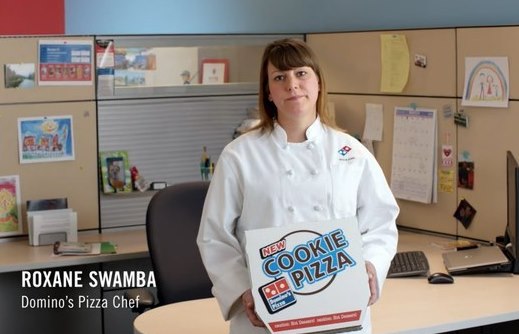

They’ve been making gains ever since. And, as Domino’s most recent campaign shows, they continue to put a human face on the brand and embrace their vulnerability. This current ad shows the head of product innovation proclaiming that “at Domino’s failure is an option.” Their willingness to fail enables them to improve their food and, says Scott Hinshaw, Domino’s EVP of operations, “that’s who we are.”

Key Insight

Why has Domino’s approach been so successful? Because it taps into an essential truth about being human. Our extensive research has shown that humans don’t become loyal to companies and brands, they become loyal to the people behind them. That’s how our brains are wired to form trust and commitment. So the more we know about the people at the companies and brands we do business with, the easier it is for us to trust and commit to them, especially if their actions and words suggest that their intentions toward us are worthy of our loyalty.

The quality we find so appealing when we encounter authentic emotions on the faces of people behind otherwise faceless corporations is what social psychologists call “concreteness.” In most of our interactions with companies and brands, concreteness is absent. Instead, we engage in an exchange based on abstractions, which direct our general behavior (making purchases), but tend not to engender true loyalty.

So when Domino’s ads included candid, unscripted footage of some the company’s key people (as opposed to food-styled images of pizza), customers could sense their genuinely humble and worthy intentions. This stimulated feelings of trust toward the company and made them more likely to try its new pizza. When complemented by a positive, concrete experience with the new pizza, both new and past customers become more committed and loyal.

Many companies have put employees in ads, but few have tapped so directly and systematically over such a long period of time into the power of human warmth and worthy intentions as Domino’s. Doing so results in the kind of loyalty attachments that can never be formed through clever advertising or celebrity spokespersons. Yet companies are often reluctant to allow their customers to “look behind the curtain” and see who they really are, though that is exactly what we crave.

Of course, Domino’s millions of customers don’t actually know Patrick Doyle, the other executives, or the company’s pizza makers personally. But by speaking the truth in their own words on the air, by expressing their commitment to us and to what they do, Doyle and his team stir something primal inside us. We want to trust the words and faces of such people. We have a human need to do so, and we feel good about ourselves when we offer them our support.

Three Ideas to Consider

- What do your customers know about the people at your company, what you care about and how it impacts the work you do? Thanks to our ubiquitous mobile devices, informal and unscripted videos are easier to create and share than ever before. Whether through your company website, newsletter or social media accounts, consider sharing some short videos that offer some insight into what you and your employees care about in life.

- When’s the last time you shared the story of a well-intentioned mistake or failure with your customers and what your company learned from it? Contrary to conventional wisdom, showing our flaws and well-meaning errors makes us more human, credible and approachable to our customers. Domino’s has earned the loyalty of millions by making light of its own shortcomings, and so can you.

- Do your advertising or sales collateral materials include photos of real executives or employees at your company? A growing body of research suggests that including these is much more credible and persuasive to customers than stock photography of generic people. Help customers associate real people with your company by bringing them out from behind the curtain of your marketing materials.